Phonological awareness and rapid naming are two skills that are often weak in struggling readers, including those with dyslexia. Let’s talk about what phonological awareness and rapid naming skills look like, how we can assess them, and if/how weaknesses in these areas can be remediated. This will be an excellent read for:

- special education teachers because you’ll improve your ability to identify students with specific learning disabilities. You’ll understand how to use assessment results to design specialized instruction.

- parents because you will understand why phonological awareness and rapid naming need to be assessed as part of a comprehensive academic evaluation when reading is an area of concern. You’ll feel confident advocating for your child by asking for these skills to be assessed by the school district.

- classroom teachers and non-special education interventionists because you’ll learn the importance of building a strong foundation in phonological awareness

This post contains affiliate links.

What are phonological awareness and phonemic awareness?

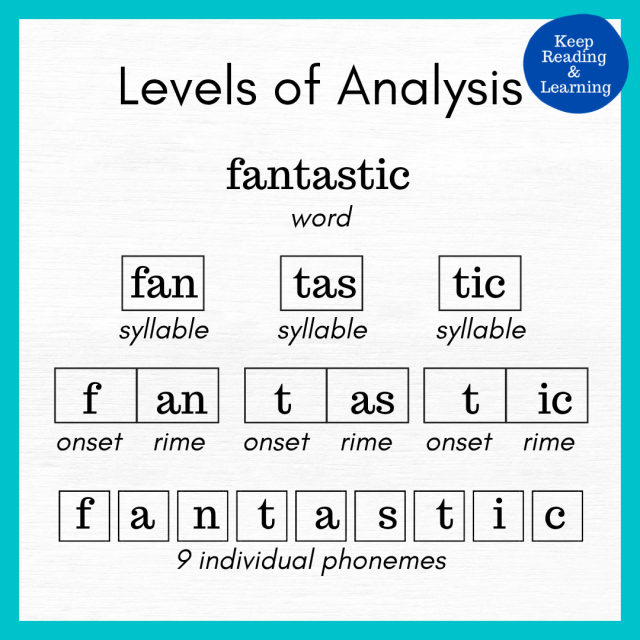

Phonological awareness is the ability to notice and manipulate speech sounds at the sentence, word, syllable, onset/rime, and phoneme levels. Examples of phonological awareness activities include counting words in a sentence, deleting a syllable from a compound word, and changing the first sound (onset) in a word to come up with a list of rhyming words.

Phonemic awareness is under the umbrella of phonological awareness. A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound, so phonemic awareness is the ability to notice and manipulate these smallest units of sound. Examples of phonemic awareness activities include blending four sounds into a word, deleting the /r/ sound from the word grass, and changing the last sound in a word to make a new word.

How do poor phonological awareness skills impact reading skills?

Phonological awareness skills have a significant impact on the development of reading skills during those crucial early stages of becoming a fluent reader: “Every point in a child’s development of word-level reading is affected by phonological awareness skills”(Kilpatrick 2015).

In simplest terms, if you want a child to read and spell all the sounds within a word, then you’ll need that child to hear all the sounds within the word.

Blending individual sounds into words is an essential skill for decoding (reading).

Segmenting a word into its individual sounds is an essential skill for encoding (spelling).

Let’s imagine we are working with a young boy named Alex. He is trying to read the word brag. He knows the primary sound for all letters so he begins by producing each sound: “/b/ /r/ /a/ /g/” but then he announces that the word is break. Alex may need practice blending phonemes into words.

Later in the day, Alex is trying to spell the word mask. He is unable to segment the word into its four individual phonemes. He sounds out the word as best as he can and writes the letters mack. Because Alex could not hear that /s/ sound when he segmented the word into phonemes, he could not write a letter to represent it. Alex may need to practice segmenting phonemes within words.

These are examples of phonemic awareness weaknesses impacting Alex at the word level. Now picture Alex trying to read a grade-level text or trying to express his ideas in writing. His reading fluency, reading comprehension, and writing fluency will be impacted by his foundational weakness in phonemic awareness.

What is rapid automatized naming?

Rapid automatized naming (RAN) is defined as “the skill of quickly accessing presumably rote information” such as numbers, letters, colors, and objects (Kilpatrick, 2015). A RAN task typically involves presenting a child with an array of visual stimuli, such as colored squares or randomized letters or numbers, and timing the child as they name the stimuli as quickly as possible.

Side note: RAN + phonological awareness are the two primary factors in the double deficit theory of dyslexia. Individuals with a deficit in phonological awareness but intact rapid naming skills tend to present with decoding weaknesses. Individuals with a deficit in naming skills but intact phonological awareness skills tend to present with fluency weaknesses. A “double deficit” in both phonological awareness and rapid naming impacts the individual’s reading speed and accuracy and is harder to remediate (Wendling & Mather, 2012).

How do poor rapid automatized naming skills impact reading skills?

Individuals with weaknesses in rapid automatized naming skills are more likely to have weaknesses in reading accuracy, reading speed, and reading comprehension (Wendling & Mather, 2012). Wendling and Mather also cite studies that indicate that kindergarten and first-grade students with RAN deficits are more likely to struggle with reading fluency in the future and that RAN performance is a predictor of a student’s ability to read irregular/exception words but not necessarily of their ability to decode phonetically regular words.

How can different educators assess phonological awareness skills?

Special education teachers and other staff responsible for formal evaluations can familiarize themselves with standardized assessments such as the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing-Second Edition (CTOPP-2) and the Phonological Awareness Test-2: Normative Update (PAT-2:NU). The Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-4 (WIAT-4) also includes a Phonemic Proficiency subtest but it assesses fewer skills than the CTOPP-2. The WIAT-4 only assesses the higher-level skills of deletion, substitution, and reversals, which means you will miss out on valuable information about the child’s ability to complete lower-level skills like blending and segmenting.

Other standardized assessments of phonological awareness are available. Kilpatrick discusses the strengths and limitations of several of them in Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties (2015). The majority of my experience is with the CTOPP-2, which is my preferred assessment. The CTOPP-2 is a standardized, norm-referenced test that measures phonological processing abilities related to reading. It includes 13 subtests that combine to measure Phonological Awareness, Phonological Memory, and Rapid Naming. Read all about it in this newer blog!

A thorough special education eligibility evaluation will certainly include an achievement test like the WIAT-4 and it’s great that the WIAT now has a measure of phonological processing but if I’m investigating a reading weakness, I always include additional measures of phonological awareness and rapid naming. The easiest way for me to do that is with the CTOPP-2. Because it also includes measures of rapid naming, I can assess these two foundational reading skills with just one additional assessment and only one additional report template!

Teachers and interventionists at any level can use David Kilpatrick’s Phonological Awareness Screening Test (PAST). It is available for free online and has four different forms for easy progress monitoring. The Phonological Awareness Skills Screener (PASS) is another option. The PAST assesses higher-level skills like deletion and substitution at the syllable onset/rime, and phoneme levels, while the PASS assesses mainly lower-level skills. PASS sections include word discrimination; rhyme recognition and rhyme production; syllable blending, segmentation, and deletion; phoneme recognition; and phoneme blending, segmentation, and deletion. I tend to use the PAST with older readers because it assesses higher-level skills. The PASS will provide me with more useful information when I’m working with younger students because it assesses lower-level skills.

There are other informal phonological awareness screeners available but I have mentioned the two I have personal experience with.

How can different educators assess rapid naming skills?

As mentioned above, the CTOPP-2 includes rapid naming tasks. If you don’t have access to the CTOPP-2, you can use the Rapid Automatized Naming and Rapid Alternating Stimulus Tests (RAN/RAS). The RAN/RAS is a quick and easy way to gain insight into a child’s rapid naming skills.

The following information comes from the publisher’s website: the Rapid Automatized Naming and Rapid Alternating Stimulus Tests (RAN/RAS) are individually administered measures designed to estimate an individual’s ability to recognize a visual symbol such as a letter or color and name it accurately and rapidly. The tests consist of rapid automatized naming tests (Letters, Numbers, Colors, Objects) and two rapid alternating stimulus tests (2-Set Letters and Numbers, and 3-Set Letters, Numbers and Colors). On all tests, the examinee is asked to name each stimulus item as quickly as possible without making any mistakes. Scores are based on the amount of time required to name all of the stimulus items on each test.

Acadience (formerly known as DIBELS) also offers free RAN assessments online. I have not personally used them because I have always had the CTOPP-2 or the RAN/RAS available to me. Teachers can use the “cut points” included in the manual to determine which students are at risk and in need of intervention.

Can we help children improve their phonological awareness skills?

Absolutely. Wendling and Mather (2012) assert that “the relationship between phonological awareness and reading ability is reciprocal and bidirectional: as phonological awareness develops, reading improves and vice versa.”

Kilpatrick (2016) shares that approximately 60-70% of children will naturally develop phoneme awareness without explicit instruction. The students who do not naturally develop it will need direct instruction. The good news is that improving phonological awareness requires a relatively modest investment of time.

Multiple researchers agree that short daily practice sessions (two to ten minutes per day of direct instruction, depending on which source you consult) have a positive impact. The National Reading Panel’s 2000 report Teaching Children to Read summarized the research by stating that effective phonemic awareness training takes anywhere from 5 to 18 total hours. If you spend ten minutes a day directly working on phonemic awareness, it could take anywhere from 30 school days to 108 school days. That may sound like a long time but if you remember that improving phonemic awareness skills may be the key to unlocking a child’s reading success, then ten minutes a day for part of the school year is 100% worth it.

Although the specifics of how to incorporate phonological awareness into your instruction are beyond the scope of this post, it’s important to mention that phonological awareness skills are best addressed in conjunction with phonics rather than alone. According to the National Reading Panel’s 2000 report, “PA training is more effective when it is taught by having children manipulate letters than when manipulation is limited to speech.” One way to combine phonics and phonemic awareness is by completing word ladders or word chains.

Can we help children improve rapid automatized naming skills?

Yes and no. Although there is no known intervention that can directly improve rapid naming skills, research has found that rapid naming skills can improve indirectly as a result of improvement in other basic reading skills, such as phonological awareness. So while a child’s performance on a RAN task can indicate that they are at risk, it does not inform our instruction beyond telling us that the child is in need of evidence-based instruction in reading. There is no benefit in having students practice rapid naming tasks by naming objects, colors, letters, etc. as quickly as possible.

I hope that this information helps you understand the roles of rapid naming and phonological awareness skills during the early stages of reading development.

Want to learn more about dyslexia? Explore my Dyslexia Resource Hub for teachers.

Receive posts like this sent straight to your inbox. Sign up below!

Sources:

Kilpatrick, David A. Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties. Hoboken, New Jersey, Wiley, 2015.

Kilpatrick, David A. Equipped for Reading Success: A Comprehensive, Step-By-Step Program for Developing Phoneme Awareness and Fluent Word Recognition. Syracuse, Ny, Casey & Kirsch Publishers, 2016.

Mather, Nancy, and Barbara J. Wendling. Essentials of Dyslexia Assessment and Intervention. J. Wiley, 2012.

National Reading Panel (U.S.) and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U.S.). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read : An Evidence-based Assessment of the Scientific Research Literature on Reading and Its Implications for Reading Instruction. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000.